How To Set Up Your Analog Zettelkasten And Numbering Systems

Getting Started Is The Hardest Part But It Gets Easier

It took me over a year to get down to the actual business of writing my first cards. I even had a couple of thousand blank 4x6 inch record cards bought and ready to go. Just the act of starting somehow held me back.

In the end, I used the outline in Scott Scheper’s book to get those first Main Category Cards written. This was in combination with watching a few videos on the topic. The main overview, which seemed to make the most sense to me, was Nicolas Gatien’s video, embedded below. This outlines the first stage of writing the Main Category Cards, before delving into where to put your Main Cards. He also discusses Bib Cards and how to deal with making notes about written sources such as books.

Watch the video, but I’ll go through the main points pertaining to Main Category Cards right now.

Main Category Cards

The top level of Category Cards can really be anything you like, and can also be numbered any way you see fit.

However, Scott Scheper and others have suggested starting a zettelkasten with a rudimentary structure. He - and I - use the list of academic disciplines as a starting point.

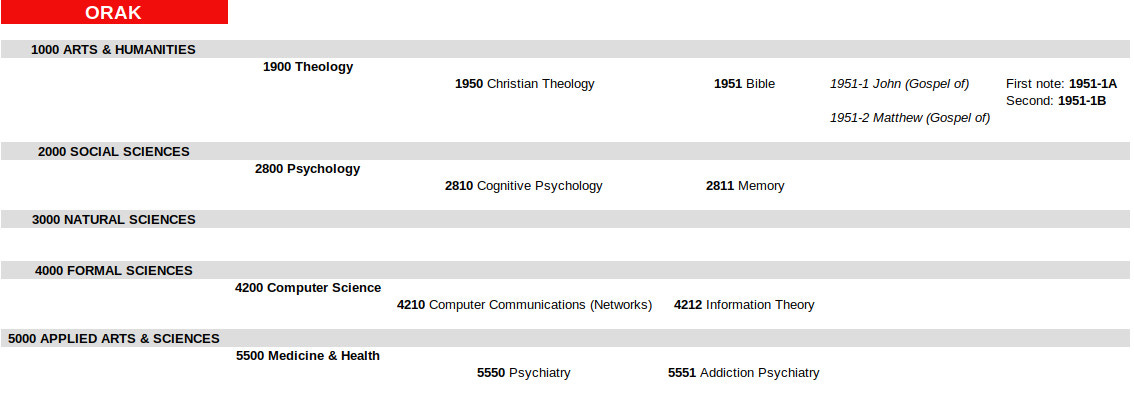

This breaks down academic subjects into five main groups: 1. Arts and Humanities; 2. Social Sciences; 3. Natural Sciences; 4. Formal Sciences; and 5. Applied Arts and Sciences.

So these five broad areas of knowledge become the structural foundation of the zettelkasten. Each of them is numbered as 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000 and 5000 respectively. The sub-disciplines within each category can then be assigned their own numbers arbitrarily.

And like following a branch from the trunk to the tip, each further sub-division number is derived from the last.

Further Numbering Of Sub-Categories

For example, in my early-phase zettelkasten, I have Arts and Humanities at 1000. I wanted to create a section for studying the Bible. This meant creating a reasonable hierarchy, at least in the beginning.

So I arbitrarily chose 1900 for the sub-discipline Theology. And because theology can be sub-divided into a number of different sub-topics, I again arbitrarily decided I would assign Christian Theology to 1950.

Finally, within Christian Theology, I opted to make 1951 my chosen number covering all things related to the Bible.

Summarising:

1000 Arts & Humanities →1900 Theology →1950 Christian Theology →1951 Bible

Here’s another example. Remember you can arbitrarily assign your own numbers to sub-disciplines and sub-sub-disciplines. It’s up to you how you do it, because in the medium and long term, the aim is to place interesting ideas (on Main Cards) near each other in the zettelkasten - and this might not necessarily mean each of these ideas are placed into discrete hierarchical positions.

So for the second example, I wanted to create a place for my study of Memory and Memorisation Techniques.

Topics That Fit Multiple Categories

This could be placed in a number of different positions in the zettelkasten. I could have opted to give this topic a home in Psychology, or Neuroscience, or even Education.

In the end, I selected Psychology - on a whim, since I was not expecting to delve directly into brain anatomy or where in the brain memories are stored. Rather to use it for practical memory training.

But having selected Psychology as its home, if in the future I do indeed feel like studying the brain anatomy aspects as they relate to memory, they’ll go into the same section on Memory (housed in Psychology).

This will allow the zettelkasten to do the magical things it is meant to do: allow cross-linking of ideas across multiple disciplines to (hopefully) seed novel and unconventional thinking and idea generation.

Okay, so where did Memory end up in my zettelkasten? Here’s the summary:

2000 Social Sciences →2800 Psychology →2810 Cognitive Psychology →2811 Memory

Main Card Numbering Systems

This kept me from starting my own zettelkasten for over a year, as I had no real idea of how to structure cards with their numbering. But the random nature of the number-picking is the thing I still needed to grasp. I guess I just like things done in a sequential, orderly and hierarchical way.

And so the advice I would give to you if you wish to start your own analog zettelkasten is: just start and don’t worry too much.

There are a few ways of numbering the main cards. I found myself gravitating towards Kathleen Spracklen’s method of using dashes and a system that employs Number-Letter-Number-Letter combinations.

So in my Bible Study section, highlighted as an example above, I got to 1951 Bible.

Then I decided to use 1951-1 as the location for the Gospel of John and its related ideas. And, for example, 1951-2 for the Gospel of Matthew. As you can see, they do not need to be ‘in order’ as they appear in the New Testament.

The Main Cards themselves will contain these numbers as the ‘home-link’, plus a letter to designate the thought or idea I am capturing. So the first idea I decide to write a card about for the Gospel of John will have the code: 1951-1A. If I wish to delve even deeper and capture further ideas that relate to this Main Card, it will go into the system at 1951-1A1, the next at 1951-1A2, etc.

If a second idea belongs to the Gospel of John, but is a separate idea strand from the first one (ie 1951-1A), then it will still belong to 1951-1 (John’s Gospel), but will not further expand on the first Main Card (1951-1A) - so it gets the next slot: 1951-1B.

Going Back To Fill Gaps!

While writing the above section on the John’s Gospel example, I realised that I might want to write general note Main Cards about “The Bible” (now housed at 1951). But, of course, I used the next numerical slot (1951-1) for the individual book of John.

So is this a problem? No. Not really. Because what number comes before 1? Zero!

If I decide to write general notes in the topic of the Bible, I’ll just give them a home at 1951-0. In fact I’ll probably just call 1951-0 a sub-category (eg Bible-General) and start the actual Main Cards with 1951-0A.

Everything is fixable with a little bootstrapping, and a really good Index. The Index Cards will be the subject of my next article on analog zettelkasten.

In the meantime, here is a very useful video of Kathleen Spracklen talking about Zettelkasten Numbering - The Easy Way. The way I have chosen to cobble my own card system together!

The Number-Letter-Number-Letter Approach Is NOT Just 4 Characters!

I confess to having a little wobble with Kathleen’s system because I took the Number-Letter-Number-Letter system to mean just four characters. Which would mean numbers 1-9 (or even 0-9) and letters A-Z.

This is not correct. It’s just a number reference followed by an alphabetical reference, etc.

So you might have a 1951-1A1C, for example. But it would be equally valid to have a card using the number: 1951-13AA21B.

In other words a number (13) followed by a letter (AA) followed by a number (21) followed by a letter (B). That’s fine!

And if required, to get similar idea threads as close as needed to each other, negative numbers are also fine.

In this case, I would be perfectly comfortable using a code such as: 1951- -1A5A, if I needed something to come before 1951-0 in my box.

That’s it.